Why I built Babblo

I speak four languages. I've reached (and lost) near fluency in several of them.

If you've experienced that, the most frustrating part isn't forgetting words entirely. It's knowing they're still in there somewhere, but not being able to retrieve them fast enough when you need them. You hesitate, simplify, and fall back to safer constructions. The language you once spoke freely starts to feel just out of reach.

Over the years, I've studied many other languages too. Some were harder than others. Russian was challenging, and sign language was probably the hardest overall because it's so different.

Looking back, what stands out is that my language learning usually progressed faster than you'd expect for the amount of effort it felt like I was putting in. I think I know why.

Speaking Always Worked Best

Out of the four languages I speak, I learned three with a strong focus on speaking from early on. The fourth, French, was different.

With French, I had a lot of grammar classes. And while grammar isn't wrong in principle, I found those classes mostly confusing and often counterproductive. What helped far more was simply going out and speaking French with my friends.

That pattern repeated itself across languages. Conversations felt like less work than studying, and they didn't feel like "learning" at all. Yet progress was faster.

Fluency, I've come to believe, doesn't come from studying language. It comes from generating it.

When you speak fluently, you're not consciously applying rules. You're not planning sentences far in advance. The correct words just come out in the correct order, and you express yourself coherently. No amount of grammar or vocabulary study can replace that kind of raw speaking practice.

Why Speaking is So Hard for Adults

As adults, we're used to expressing ourselves clearly. In a foreign language, we suddenly struggle to form sentences that a four-year-old native speaker could say effortlessly. It's humbling, and often embarrassing.

It doesn't really matter whether others are patient or encouraging. Even if they know you're learning, you still feel foolish.

Children don't have this problem. They speak badly all the time, including in their native language, and we forgive them for it. Most people think their mother tongue "came easily," but they've simply forgotten the years of struggle.

Language as a Generative System

Native speakers don't apply grammar rules when they speak. They generate language on the fly. Word order, agreement, idiomatic phrasing, it all emerges automatically.

In that sense, language is less like a set of rules and more like a generative system you internalize over time.

This is where the analogy with large language models is useful. An LLM doesn't "know grammar" either. It has a strong statistical model of a language: which words tend to follow which others, which sentence structures sound natural, which combinations feel idiomatic. Jeff Hawkins explored a similar idea about the brain as a prediction machine in his book On Intelligence, which I found compelling even before LLMs existed.

A human learner is building something similar, just more slowly. At first the model is crude. Over time it improves. With fluency, generation feels automatic.

Why Speech Reveals the Real Model

Writing gives you time. You can pause, rewrite, and correct yourself. That's useful, but it hides a lot.

Speaking doesn't allow that luxury.

Speech is just-in-time generation. You either produce the sentence correctly right now, or you feel foolish and the conversation moves on without you. Because of that, everything leaks out: hesitation, avoidance, over-reliance on safe constructions, repeated grammatical patterns, and gaps in idiomatic phrasing.

If you listen to someone speak for a few minutes, you learn far more about their real level than you ever would from a written exercise.

Speech is where your true language model is exposed.

The Intermediate Plateau

This also explains why so many learners get stuck at the intermediate level.

Early on, feedback is obvious and frequent. Later, it becomes subtle and precise. But in the middle, feedback turns generic. You feel like you "already know this," and studying becomes inefficient.

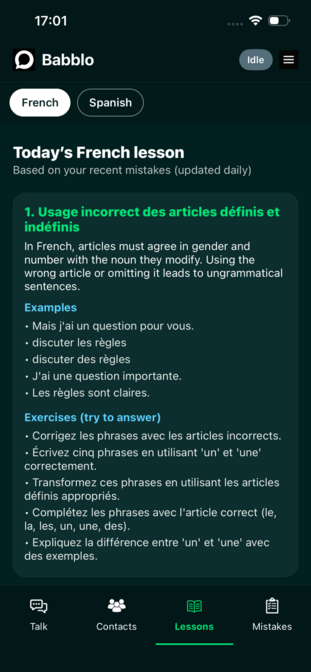

At that stage, each learner's internal model has its own specific flaws. Broad learning material stops helping. Progress requires targeted attention, not more content.

Why I Built Babblo

LLMs made something possible that hadn't been before: listening to spoken language, capturing errors automatically, and grouping them into meaningful patterns.

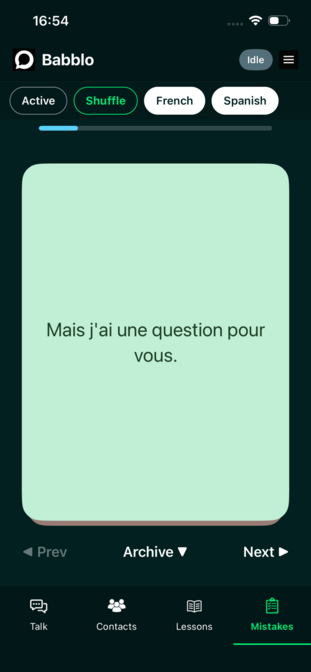

That's what Babblo does.

It encourages you to speak, compares that output to a strong model of the language, and highlights the biggest blockers holding you back.

It reflects how I actually learned languages: by speaking, by making mistakes, getting corrected, and by gradually refining an internal model until fluency felt natural.

If this way of thinking about language resonates with you, you might find Babblo useful too.

For more on what counts as intelligence in machines versus humans, see Opus 4.5 is smarter than my dog.